Talking Tails.

The paper: Siniscalchi et al. (2013) Seeing Left- or Right-Asymmetric Tail Wagging Produces Different Emotional

Responses in Dogs. Current Biology 23:1-4. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2013.09.027

Subject areas: Animal Behavior

Vocabulary:

Left-right asymmetry – although externally, most animals appear very close to symmetric when comparing left and right sides, the fact is that internally, there is a consistent theme of asymmetry in structure and function. In humans, this easily seen in the position of the stomach to the left of the body and with the lungs – structures you might expect to be symmetrical but in fact the left lung has one fewer lobes than the right one.

—–

This article is a summary of a recent primary research paper intended for high school teachers to add to their general knowledge of current biology, or to supplement their lessons by showing students the kinds of projects that current biological research addresses.

—–

Today’s paper again explores animal behavior and again with a fairly accessible experiment – this time a bit closer to home than the loggerheads – in pet dogs. Siniscalchi and colleagues have explored asymmetries in tail-wagging behavior. A previous study by this group showed that a dog would consistently wag its tail towards its right side when given a friendly stimulus that causes it to want to approach (e.g. seeing the dog’s owner), but wag its tail more towards the left side when presented with a stimulus that causes withdrawal (e.g. seeing a dominant unfamiliar dog). Assuming that the tail wags have a purpose and may be a communicative behavior, the authors decided to look into recognition behavior of the tail wags. That is, whether or not dogs will consistently react to either a rightward or leftward wag.

How they tested

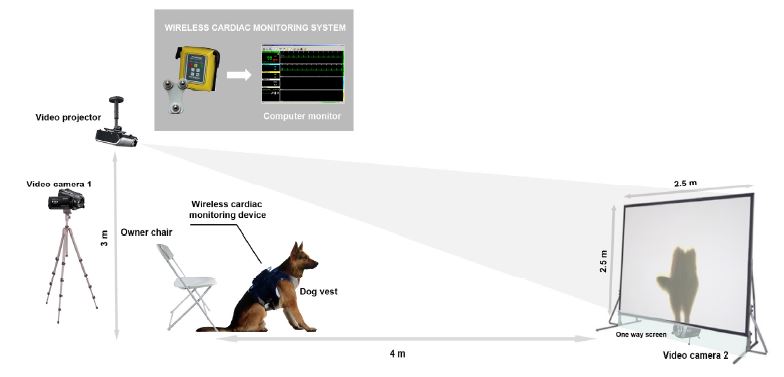

The experimental setup is depicted here:

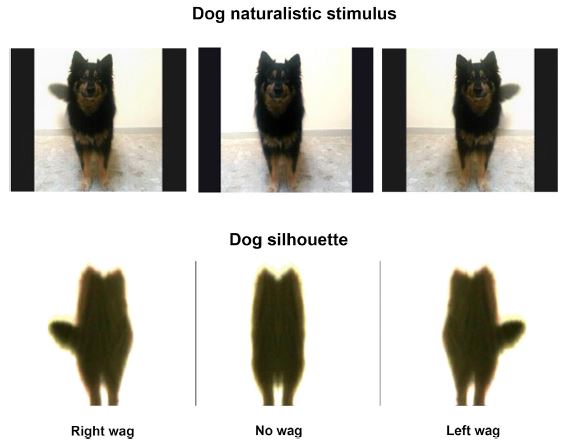

Test subjects were 43 dogs (ages 1-11 years, pure- and mixed- breeds, males and females) that were living as pets and had never been tested in this kind of experiment before. They wore vests that held wireless heart monitors, and sat next to their owners, who were also seated, in front a projection screen. The test stimuli were either a projection of actual dogs wagging their tails in either direction, or a black silhouette of dogs doing the same.

The behavior and heart rate of the dogs were recorded and then analyzed by two trained observers who did not know the parameters of the experiment and were only assessing the behavioral state of the dogs: relaxed/neutral, stress/anxiety, alert/targeting.

What they found

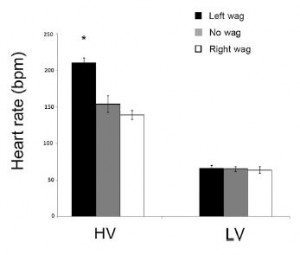

The figure at right shows the average maximum (HV) and minimum (LV) heart rate of the tested dogs. Not surprisingly, the minimum heart rate remained the same no matter what stimulus was presented. However, there is a significant increase in maximum heart rate in the dogs observing a left-wagging dog. The results were consistent between presentations of a naturalistic dog wagging its tail and presentations of tail-wagging silhouettes.

The figure at right shows the average maximum (HV) and minimum (LV) heart rate of the tested dogs. Not surprisingly, the minimum heart rate remained the same no matter what stimulus was presented. However, there is a significant increase in maximum heart rate in the dogs observing a left-wagging dog. The results were consistent between presentations of a naturalistic dog wagging its tail and presentations of tail-wagging silhouettes.

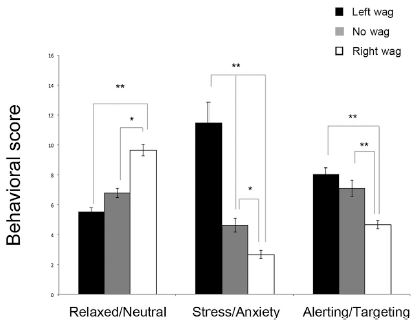

The other analysis of the experiment focused on observed behaviors that indicate the dogs’ emotional states. In the figure below, the grey bars represent the control stimulus of a dog not wagging its tail. When observing dogs wagging leftward (black bars), the stress behaviors of the observers increase over no-wag. Although the bars are different, there are not significant changes in the level of relaxed behaviors or alerting behaviors. When observing rightward tail wags (white bars), there is a significant increase in relaxed behaviors, and significant decreases in both stress and alerting behaviors.

What it means

This experiment suggests that dogs are able to communicate with their tail wags. Previously, wagging of the tail could be matched with particular stimuli. Now, they have shown that other dogs can read the tail wags and react appropriately. Leftward tail wags appear to convey a higher state of alertness or anxiety, while rightward tail wags indicate a more relaxed state. There were no significant differences by breed, sex, or age.

Siniscalchi and his colleagues are interested in left-right asymmetries in the brain and how they relate to asymmetries in social behavior. Although this finding does not make any substantive link between the asymmetry in brain structure or function and asymmetry in behavior, it does establish an asymmetry in the type of information conveyed and understood by the dogs. The next step would be to see whether there is asymmetric brain activity when relaxing or stressful stimuli are presented.

No comments

Be the first one to leave a comment.