Sex, death, and large testes.

Subject areas: Evolution, Reproductive Biology

Vocabulary:

marsupials – a group of mammals that have external pouches in which newborns are protected and nurtured, in part because unlike most mammals, they are born after a very short gestation and are much less developed than newborns of other species. Common marsupials are the kangaroo and koala, and here in the United States, the opossum.

—–

This article is a summary of a recent primary research paper intended for high school teachers to add to their general knowledge of current biological research, or to supplement their lessons by showing students the kinds of projects that current biological research addresses.

—–

While dating and sex can sometimes be stressful for humans, in most cases, it is not dangerous. In some other parts of the animal kingdom, however, it can actually be fatal! Perhaps the best known example is the case of the arthropod, Latrodectus, or the black widow spider: the female spider often eats the male after copulation. Praying mantises are also popularly known for this behavior, but that may be due to laboratory conditions, rather than a normal event in the wild. We do not usually think of mammalian reproduction as being similarly dangerous to one of the partners. But in fact, in an entire family of marsupials, the Dasyuridae, the males engage in semelparity, or suicidal reproduction. They are also the only mammals that do that. Although Dasyuridae includes tasmanian devils, most of the family are much smaller, but all are carnivores, hunting for and eating insects.

Given the requirement for maternal care of newborn/young, one would expect that mammals generally have a low maximal reproductive rate (even large litters of mammals do not come close to the numbers of young born to some fishes, or insects, or many other classes of animals). So why, with such a low rate of reproduction, would a mammalian species limit males to a single copulation? How could that be reproductively successful enough to have evolved? Fisher et al investigated details of over 50 species of Dasyuridae to try to determine the answer to that question.

What they knew.

There is actually a range of behaviors among the Dasyuridae of Australia, South America, and Papua New Guinea. For 52 species studies, some species had normal male mortality rates and essentially no semelparity, while in a few species, all males die shortly after copulation due in part to immune system shutdown. Other species lie in between, and the investigators classified them into 5 groups, from 1 being most extreme to 5 being completely iteroparous (survive to copulate again).

The most likely explanation for semelparity in the dasyurids but not other similar small mammals, proposed by Braithwaite and Lee in 1979, is that environmental issues make male survival extremely unlikely after a year of maturity and thus putting their whole life into one act of copulation might increase reproductive success, and wouldn’t be any worse, from a reproductive standpoint, than surviving for a while but probably dying before the next mating season anyway. In fact, their continued survival could even take resources away from pregnant females or young pups.

Another possibility has to do with mate preference. One theory was that there was aggressive, potentially near-fatal fighting among young males to establish dominance or attract a mate. However, very few cases of such pre-copulatory aggression have been documented in these marsupials. A better theory is that sperm competition somehow favors semelparity. Sperm competition means that females are inseminated by more than one male before fertilization, and the sperm from multiple donors will compete to fertilize the egg. There is already strong evidence of sperm competition in a number of dasyurid species.

What they did.

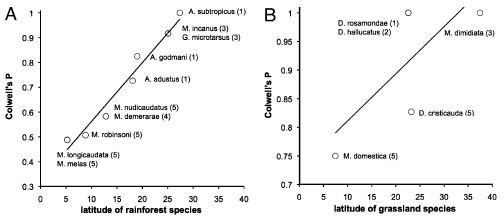

If you look at the figures, it looks like a fairly straightforward set of experiments. The first figure deals with prey availability. They researchers looked first at seasonal predictability of prey availability by counting the numbers of prey at sites that were known to be inhabited by dasyurids. They found that the higher the latitude, the more consistent the numbers of arthropod prey (bugs to eat).

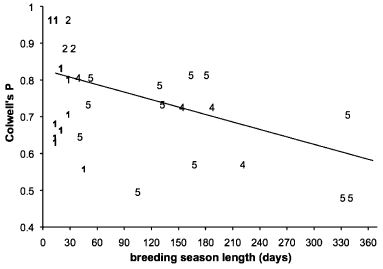

What the first figure shows is a correlation between predictability of prey abundance (not necessarily how much is available, but how consistent that number is year to year) and the level of “sexual suicide” in male dasyurids. There is a direct correlation between the latitude at which the dasyurids are found and their level of male death upon copulation. That is, dasyurids who live at higher latitudes are more likely to die during or shortly after mating. Coincidentally, the higher latitudes also have the highest predictability in prey availability.

Next, they looked at the amount of time available to breed. There is a pronounced difference in that the species with the highest level of postcoital death also had the shortest breeding season. Some of the more iteroparous species also had short breeding seasons, but on average they were significantly longer. It was also noted that males of semelparous species copulate over twice as long as males of other species (9.4 hours vs 3.7 hours).

Next, they looked at the amount of time available to breed. There is a pronounced difference in that the species with the highest level of postcoital death also had the shortest breeding season. Some of the more iteroparous species also had short breeding seasons, but on average they were significantly longer. It was also noted that males of semelparous species copulate over twice as long as males of other species (9.4 hours vs 3.7 hours).

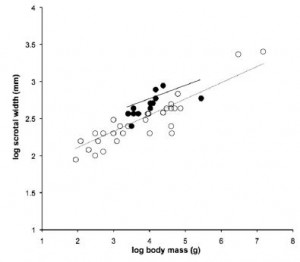

Finally, in Figure 3, they have measured and plotted a correlation of scrotal width to body mass. This is a slightly confusing graph, but basically, the black dots are males from species that experience high (level 1) semelparity, and the white circles are a mix of all other levels of semelparity/iteroparity. The thing to note is the two regression lines. The solid line shows that the scrotal size (relative to body size) of the semelparous species is larger than the scrotal size of more iteroparous species.

Finally, in Figure 3, they have measured and plotted a correlation of scrotal width to body mass. This is a slightly confusing graph, but basically, the black dots are males from species that experience high (level 1) semelparity, and the white circles are a mix of all other levels of semelparity/iteroparity. The thing to note is the two regression lines. The solid line shows that the scrotal size (relative to body size) of the semelparous species is larger than the scrotal size of more iteroparous species.

What does that all mean?

First, in the species that have high semelparity, the breeding period is short, and as it turns out, linked strongly to a very predictable food source as well. The food availability peaks just after most of the young are weaned and the females have stopped lactating. This is a condition that could understandably lead to a short and well-timed mating season.

How do the males adapt to the females’ short estrus? Because of the limited time in which to copulate, competition among males increases. As mentioned before, this does not manifest as behavioral aggression. Instead, there is sperm competition. This is supported by the longer copulation time (preventing other males from courting the female) and larger relative testes size (and therefore higher numbers of sperm deposited in the female). The post-coital lethality is most likely a side effect of having evolved larger testes. Since it is likely the males would not make it to the next reproductive cycle anyway, the lethality is not a trait that would be selected against by evolution. It is also unlikely that the death of the males causes any meaningful increase in survival of the females or young, whether by increasing food availability or otherwise.

![A western quoll, dayurus geoffroi. By Nezumi Dumousseau [CC-BY-2.5], via Wikimedia Commons](http://www.axopub.com/wp01/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/Dasyurus_geoffroii.jpg)

No comments

Be the first one to leave a comment.